Cassava Manihot esculenta Crantz Overview (2022)

1A. Introduction

The cassava is a plant extensively cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, including Latin America, Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and more. It is the third-largest source of food carbohydrates in the tropics, behind rice and corn. Colonized in Brazil over 10,000 years ago and introduced to the rest of the world by Portuguese colonists, the cassava now supports the livelihood of over 500 million people. It has a wide variety of uses despite being toxic without proper preparation (Shigaki, 2016).

1B. The Cassava

The Manihot esculenta Crantz, known primarily as cassava, is a shrub native to South America. It is also known as manioc, yuca, tapioca, as well as other niche regional names. Its scientific name was coined by Austrian-Luxembourgish botanist Heinrich Johann Nepomuk von Crantz, hence the Crantz in its name. It’s often known for its tuberous root which is used in a variety of diets in the tropics. The starch from the roots of cassava has many dietary and industrial applications.

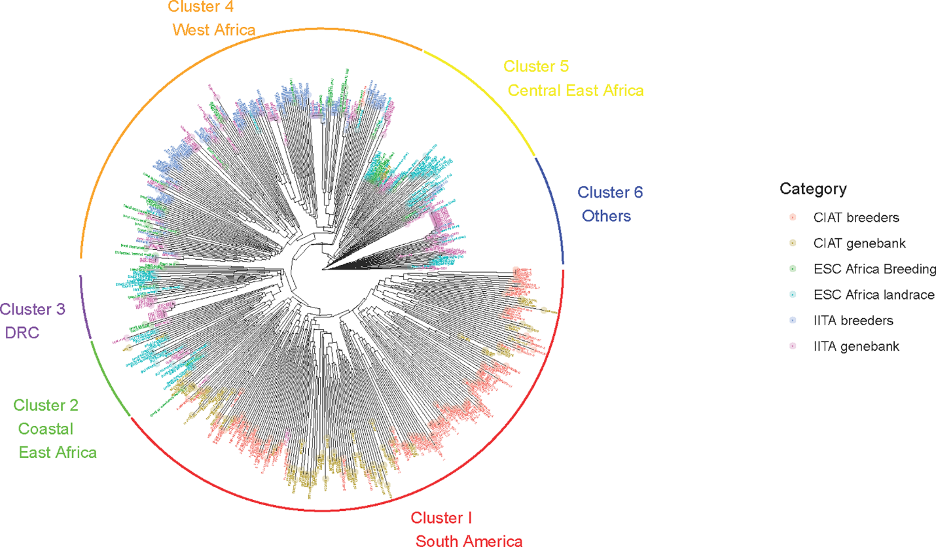

The Manihot genus to which Manihot esculenta belongs has over 100 species, all averaging 1-4 metres in height. There are two primary types: spreading types and erect types. Each cassava variant differs from one another quite drastically, as there is a high degree of interspecific hybridization and cross-breeding (Figure 1). There are several germplasm banks—storage facilities for seeds to preserve genetic diversity—around the globe, with the largest at the Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical in Colombia. These germplasms are necessary since there are so many different varieties of cassava variants, all originating from and grown in different climates. For example, in Brazil’s habitats alone, there are germplasms of lowland and highland semi-arid tropics, lowland humid tropics, and lowland hot savannah (Alves, 2001).

The cassava root is a true root and not tuberous as its common description suggests. Tuberous roots are considered “modified roots”, which means it cannot be used in propagating vegetation. A mature cassava root has three distinct tissue types: bark, peel, and parenchyma. The peel layer makes up about 11-20% of the total root weight, while the parenchyma make up approximately 85%. While the cassava plant does possess stems, leaves, and flowers; its roots are the main and largest organs. The roots’ parenchyma is the edible portion, consisting primarily of starch cells.

While it is grown all over the tropical and subtropical regions of the world as a food source, the natural cassava plant is poisonous and carries a high cyanide content. If not prepared correctly, the raw unprocessed plant can kill a human if it is consumed in large enough quantities. Consumption of large doses of cyanide can cause cyanide poisoning, vomiting, goitre and diarrhoea, and potentially death (Ndubuisi & Chidiebere, 2018). Two “cultivars” or variants are most commonly grown on farms: the ‘sweet’ cultivar and the ‘bitter’ cultivar (Alves, 2001). ‘Sweet’ cultivars cassava can produce 20 milligrams of cyanide per kilogram of fresh cassava; while ‘bitter’ cultivars produce over 5 times as much, at a rate of 1 gram of cyanide per 1 kilogram of fresh root (Ndubuisi & Chidiebere, 2018).

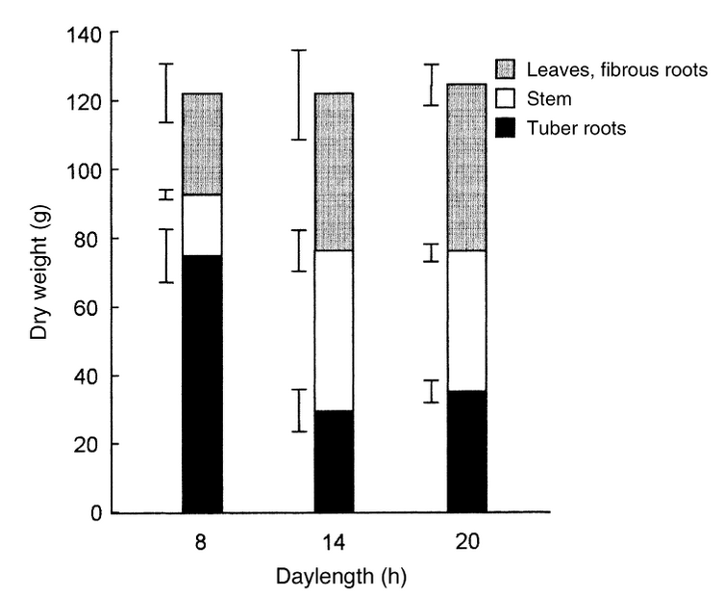

As stated before, environmental factors can affect the cassava’s physiology and morphology. It’s grown in a wide variety of climates: from 30 degrees North to 30 degrees South latitudinally, from sea level to 2,300 metres high, from arid areas with less than 600 millimetres of rainfall a year to humid tropics with over 1,500 millimetres of rainfall per year. One major environmental factor that can greatly affect cassava growth is temperature. Cassava sprouting is impaired at temperatures below 17°C and above 37°C, while the optimal temperature is between 28.5° and 30°C. Ideal temperature ranges also differ for plants grown in greenhouses versus plants grown in the field, at 25°-30°C and 30°-40° respectively for optimal growth (Alves, 2001). Another factor that can affect growth is the abundance of light, which manifests in day lengths. In regions where the day lengths don’t change much, varying from 10-12 hours per day, there are little cassava root production differences. However, in regions where the days are slightly shorter, cassavas have been shown to grow short shoots and have more storage root development (Figure 2).

Since Manihot esculenta is widely grown around the world, it’s also a major target for certain pests, such as the cassava-whitefly (Bemisia tabaci), the cassava green mite, the variegated grasshopper, and the cassava mealybug. These pests can cause cassava brown streak disease (CBSD), cassava mosaic disease (CMD), and other diseases that can cause serious outbreaks in rural areas without proper medical support (IITA).

1C. Cassava and People

The cassava is primarily used as a food source. It is abundant in carbohydrates, calcium, vitamins B and C, and minerals. However, many factors may contribute to a variable amount of nutrients.

Domestication of cassava began around 7,000 BC. By the time colonists had arrived in the New World, the crop was already being planted and harvested throughout tropical America to feed indigenous populations (Alves, 2001).

Manihot esculenta is often planted in multi-cultures by small farmers and intercropped with other vegetables, plantation crops, or legumes. Fertilizer is rarely used due to the small scale of the farms and a lack of availability in rural areas. On small family farms, cassava is often grown only to eat. However, on larger-sized farms, often in Mozambique and Nigeria, the tuberous root can also be grown to be used for industrial purposes (IITA).

Fresh cassava can be skinned and peeled before being cooked to remove the natural cyanogens in the plant. In Africa, it can be boiled, fried, or baked and then eaten with fish or other meats. In Brazil, the sweet cultivar of cassava can be peeled and cooked in syrup to make a soup, called cocido. There are numerous other culinary uses for cassava around the world, including but not limited to fufu (steamed or boiled peeled roots pounded together with dough) from Ghana, mingao (a drink made from dissolved fermented starch and water) from the Amazon region, dumby (boiled cassava tubers, cut into pieces and eaten with soup) from Liberia, tiwul (pulverized and sieved dried cassava substitute for rice) from Indonesia, and more. The list goes on and on (Alves, 2001).

In industrial areas that mass produce cassava like Mozambique and Nigeria, cassava roots can be made into animal feed via a silage technique (Alves, 2001). Silage is a type of animal feed, often used as a substitute to hay in regions that grow more cassava than wheat (USAID). Thailand exports cassava to Europe as dried chips for animal feeding; same for Indonesia with their gaplek (dried cassava roots). In culinary-based factories, cassava is industrially processed and the starch is extracted from the roots to use in cassava flour, starch-based adhesives, glucose and dextrose through chemical processes, and more. Some regions even produce biodegradable plastics from the starch extracted from cassava roots (Alves, 2001).

1D. History and utilization of cassava in Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso, a country located in West Africa, nestled between Mali, Niger, Benin, Togo, Ghana, and Cote d’Ivoire, first had access to cassava when it was brought over from the New World by colonists. It was made widespread a few decades in the past and has inspired the formation of cassava processing units as well as several regions that focus entirely on growing and cultivating cassava. With irrigation systems, cassava is farmed in Burkina Faso in both rainy and dry seasons. Its most popular product is a side dish called acheke or attiéké—made from grating fermented cassava pulps or dried (Guira et al., 2017).

There are two primary ways that cassava was introduced into Burkina Faso: via Roman Catholic white missionaries and locals from the Gold Coast and Cote d’Ivoire. Because Burkina Faso was a historically poor country, especially after French colonizers came and made it a territory, the government introduced cassava as a way to reinvigorate the economy and give small family farmers a crop to cultivate and grow. Starting in 1987, Burkinabé people were allowed to begin experimenting with farming methods with cassava in the Hauts-Bassins region (Guira et al., 2017).

Since most of Burkina Faso’s cassava farms are small family ranches, cassava production combines to less than 10 tons annually. The availability also differs from region to region. In the South West region, there is more of the improved variety, slated more for industrial processing; as opposed to the Center East region’s original varieties that are used for culinary purposes. (Table 1)

| Identifier | Variety names | Locality | Cycle (months) | Average stalk height (m) | Leaves morphology | Root and other characteristics | Toxicity (according to farmers) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banchii, Manchien | Banfti | Centre West (Sanguié) | 12-18 | 0.2-0.5 | Red leafstalk | Big tubers, threadlike, white, explode to cooking | No |

| Santidougou local variety | NIV | Hauts-Bassins (Santidougou, Desso) | 9-12 | 2-3 | Red leafstalk | Big and long | No |

| Bounou (White cassava) | Bounou | Centre West, Cascades, South West | 5-6 | 1-2.5 | Red leafstalk, large leaf | Big and long | No |

| Banké (V2) | V2 | Boucle du Mouhoun | 10-12 | 1-2.5 | Large leaf | Threadlike, whitish | No |

At a household level, cassava is used primarily for human food in Burkina Faso. Animals are often fed leaves and root peels, but not meaty tuberous roots. Burkinabé households’ meals range from boiled roots and raw roots to cassava flour and attiéké. The only additives involved are salt and sometimes an additional fermentation process.

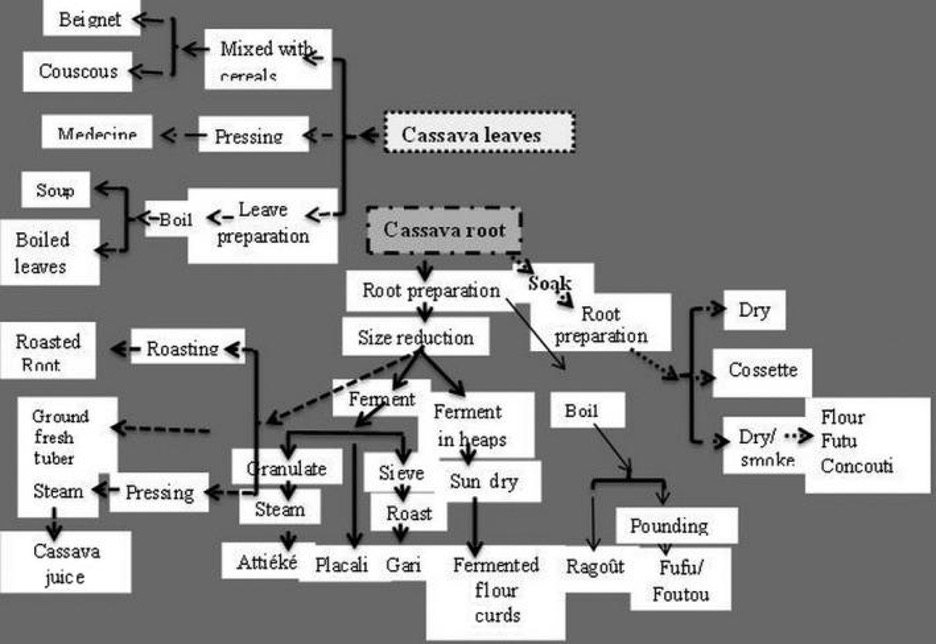

In the aforementioned processing units, workers take raw cassava and convert it into gari, tapioca, flour, cossette, starches, and more. Attiéké remains the most processed product by far. Final products are either consumed directly in local villages or sold to neighbouring countries like Mali or Senegal. There are many uses for the other leftover parts of the cassava plant as well, like using cassava leaves for medicine or making soup, juice, and more. (Figure 3)

1E. Summary

The cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) originated from Brazil but was spread all over the tropical and subtropical world via colonist ships. It is the third most common source of carbohydrates in the tropical world, right behind rice and maize. Cassava has many different uses, from culinary items both simple and complex to industrial processes like animal feed and starch flour. It is a popular plant in rural communities, with a vast range of research and experimentation on its germination, growth, and uses. Cassava is also used in small- and medium-scale industrial processing plants to make a variety of products like silage, flour, etc. However, it is not perfect nor entirely safe as its raw form contains trace amounts of cyanide, enough to kill a human if not processed correctly.

1F. References Cited

Alves, A. A. (2001). Cassava botany and physiology. In Cassava: biology, production and utilization (pp. 67-89). CABI. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851995243.0067.

Ferguson, M. E., Shah, T., Kulakow, P., Ceballos, H. (2019). A global overview of cassava genetic diversity. PLoS ONE, 14(11): e0224763. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224763.

Guira, S. K., Kabore, D., Sawadogo-Lingani, H., Traora, Y., Savadogo, A. (2017). Origins, production, and utilization of cassava in Burkina Faso, a contribution of a neglected crop to household food security. Food Sciences & Nutrition, 5(3), 415-423. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.

IITA. Cassava (Manihot esculenta). International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. (n.d.). Retrieved September 21, 2022, from https://iita.org/cropsnew/cassava.

Isendahl. (2011). The Domestication and Early Spread of Manioc (Manihot Esculenta Crantz): A Brief Synthesis. Latin American Antiquity, 22(4), 452-568. https://doi.org/10.7183/1045-6635.22.4.452.

Ndubuisi, N. D., Chidiebere, A. C. U. (2018). Cyanide in Cassava: A Review. Int J Genom Data Min, 118. https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-0616.000118.

Pujol, G. G., Laurent, G., Pinheiro-Kluppel, M., Elias, M., Hossaert-McKey, M., McKey, D. (2002). Germination Ecology of Cassava (Manihot Esculenta Crantz, Euphorbiaceae) in Traditional Agroecosystems: See and Seedling Biology of a Vegetatively Propagated Domesticated Plant. Economic Botany, 56(4), 366-379. https://doi.org/10.1663/0013-0001(2002)056[0366:GEOCME]2.0.CO;2.

Shigaki, T. Cassava: The Nature and Uses,

Editor(s): Benjamin Caballero, Paul M. Finglas, Fidel Toldrá,

Encyclopedia of Food and Health, Academic Press, 2016, Pages 687-693, ISBN 9780123849533,

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-384947-2.00124-0.

United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Silage Making for Small Scale Farmers. (n.d.). Retrieved September 23, 2022, from https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs.PNADQ897.pdf.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Cassava plant guide – USDA. (n.d.). Retrieved September 22, 2022, from https://plants.usda.gov/DocumentLibrary/plantguide/pdf/pg_maes